The SHAPforxgboost package

I wrote the R package SHAPforxgboost to cover all the plotting functions illustrated in this post. This post serves as the vignette for the package.

Please install from CRAN or Github.

install.packages("SHAPforxgboost")

# or

devtools::install_github("liuyanguu/SHAPforxgboost")Why SHAP values

SHAP’s main advantages are local explanation and consistency in global model structure.

Tree-based machine learning models (random forest, gradient boosted trees, XGBoost) are the most popular non-linear models today. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values is claimed to be the most advanced method to interpret results from tree-based models. It is based on Shaply values from game theory, and presents the feature importance using by marginal contribution to the model outcome.

This Github page explains the Python package developed by Scott Lundberg. Here we show all the visualizations in R. The xgboost::xgb.shap.plot function can also make simple dependence plot.

Local explanation

# run the model with built-in data

suppressPackageStartupMessages({

library("SHAPforxgboost"); library("ggplot2"); library("xgboost")

library("data.table"); library("here")

})

y_var <- "diffcwv"

dataX <- as.matrix(dataXY_df[,-..y_var])

# hyperparameter tuning results

param_list <- list(objective = "reg:squarederror", # For regression

eta = 0.02,

max_depth = 10,

gamma = 0.01,

subsample = 0.95

)

mod <- xgboost::xgboost(data = dataX,

label = as.matrix(dataXY_df[[y_var]]),

params = param_list, nrounds = 10,

verbose = FALSE, nthread = parallel::detectCores() - 2,

early_stopping_rounds = 8)

# To return the SHAP values and ranked features by mean|SHAP|

shap_values <- shap.values(xgb_model = mod, X_train = dataX)

# The ranked features by mean |SHAP|

shap_values$mean_shap_score## dayint Column_WV AOT_Uncertainty dist_water_km aod

## 0.0165331533 0.0115615699 0.0073583570 0.0057172670 0.0039983764

## elev DevAll_P1km RelAZ forestProp_1km

## 0.0037026883 0.0025215052 0.0009489252 0.0003197501SHAP values are calculated for each cell in the training dataset. The SHAP values dataset (shap_values$shap_score) has the same dimension (10148,9) as the dataset of the independent variables (10148,9) fit into the xgboost model.

The sum of each row’s SHAP values (plus the BIAS column, which is like an intercept) is the predicted model output. As in the following table of SHAP values, rowSum equals the output predict(xgb_mod). I.e., the explanation’s attribution values sum up to the model output (last column in the table below). This is the case in this example, but not so if you are running e.g. 5-fold cross-validation.

# to show that `rowSum` is the output:

shap_data <- copy(shap_values$shap_score)

shap_data[, BIAS := shap_values$BIAS0]

pred_mod <- predict(mod, dataX, ntreelimit = 10)

shap_data[, `:=`(rowSum = round(rowSums(shap_data),6), pred_mod = round(pred_mod,6))]

rmarkdown::paged_table(shap_data[1:20,])This offers model explanation for each observation in the dataset. And offers lots of flexibility when summarizing the whole model.

Consistency in global feature importance

And why feature importance by Gain is inconsistent

Consistency means it is legitimate to compare feature importance across different models. When we modify the model to make a feature more important, the feature importance should increase. The paper used the following example:

paper 2, S. Lundberg 2019 arXiv:1905.04610

Use the dataset of Model A above as a simple example, which feature goes first into the dataset generates opposite feature importance by Gain: whichever goes later (lower in the tree) gets more credit. Notice below the feature importance from xgb.importance were flipped.

library(xgboost)

d <- data.table::as.data.table(cbind(Fever = c(0,0,1,1), Cough = c(0,1,0,1), y = c(0,0,0,80)))

knitr::kable(d)| Fever | Cough | y |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 80 |

X1 = as.matrix(d[,.(Fever, Cough)])

X2 = as.matrix(d[,.(Cough, Fever)])

m1 = xgboost(

data = X1, label = d$y,base_score = 0, gamma = 0, eta = 1, lambda = 0,nrounds = 1, verbose = F)

m2 = xgboost(

data = X2, label = d$y,base_score = 0, gamma = 0, eta = 1, lambda = 0,nrounds = 1, verbose = F)

xgb.importance(model = m1)## Feature Gain Cover Frequency

## 1: Cough 0.6666667 0.3333333 0.5

## 2: Fever 0.3333333 0.6666667 0.5xgb.importance(model = m2)## Feature Gain Cover Frequency

## 1: Fever 0.6666667 0.3333333 0.5

## 2: Cough 0.3333333 0.6666667 0.5m1 and m2:

Model m1:

m2:

Moreover, comparing Model B to Model A in the figure above, Model B’s output was actually revised in a way that it relies more on a given feature (Cough, output scores increased by 10), so cough should be a more important feature. While Gain still get it wrong, SHAP reflects the correct feature importance.

SHAP plots

Summary plot

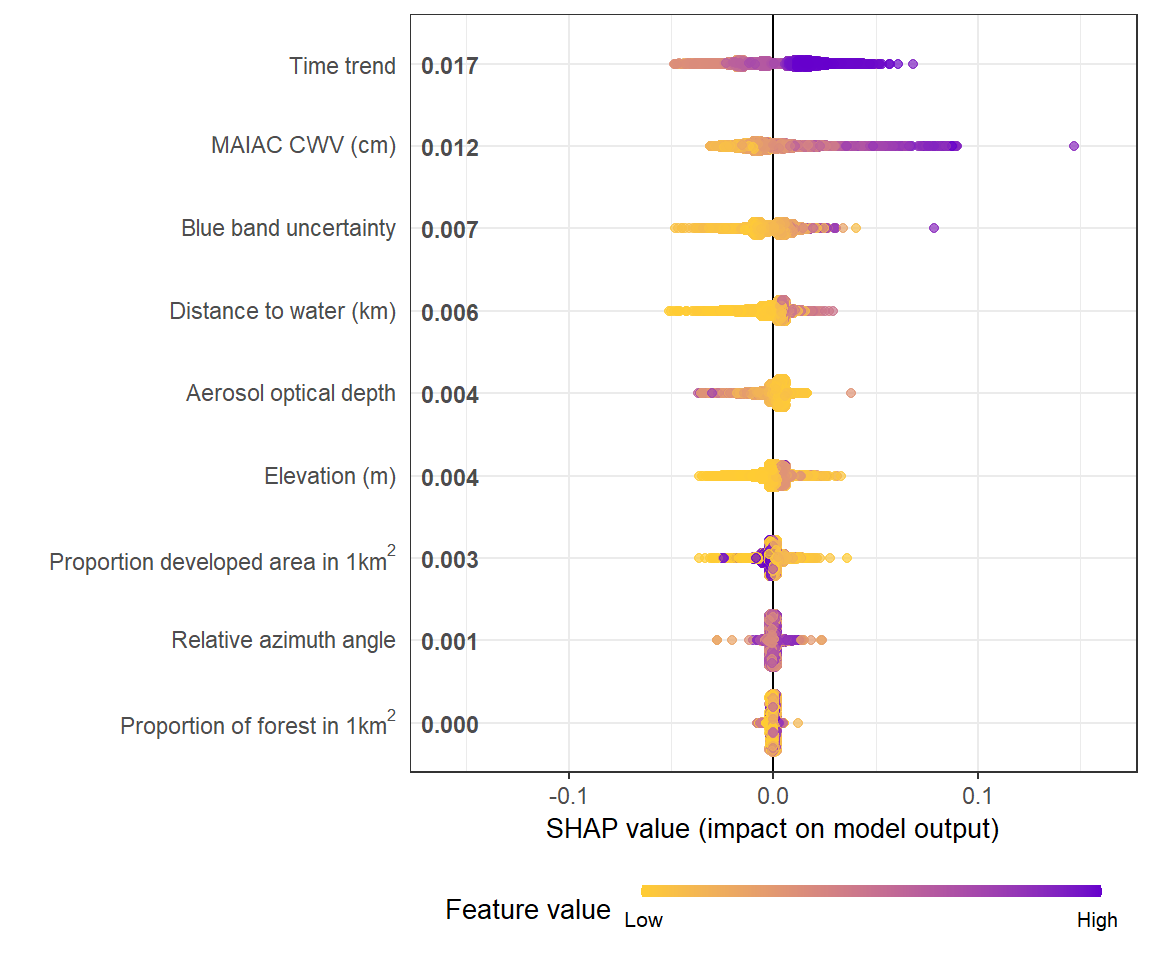

The summary plot shows global feature importance. The sina plots show the distribution of feature contributions to the model output (in this example, the predictions of CWV measurement error) using SHAP values of each feature for every observation. Each dot is an observation (station-day).

# To prepare the long-format data:

shap_long <- shap.prep(xgb_model = mod, X_train = dataX)

# is the same as: using given shap_contrib

shap_long <- shap.prep(shap_contrib = shap_values$shap_score, X_train = dataX)# **SHAP summary plot**

shap.plot.summary(shap_long)

Alternative ways to make the same plot:

# option 1: from the xgboost model

shap.plot.summary.wrap1(model = mod, X = dataX)

# option 2: supply a self-made SHAP values dataset (e.g. sometimes as output from cross-validation)

shap.plot.summary.wrap2(shap_score = shap_values$shap_score, X = dataX)Dependence plot

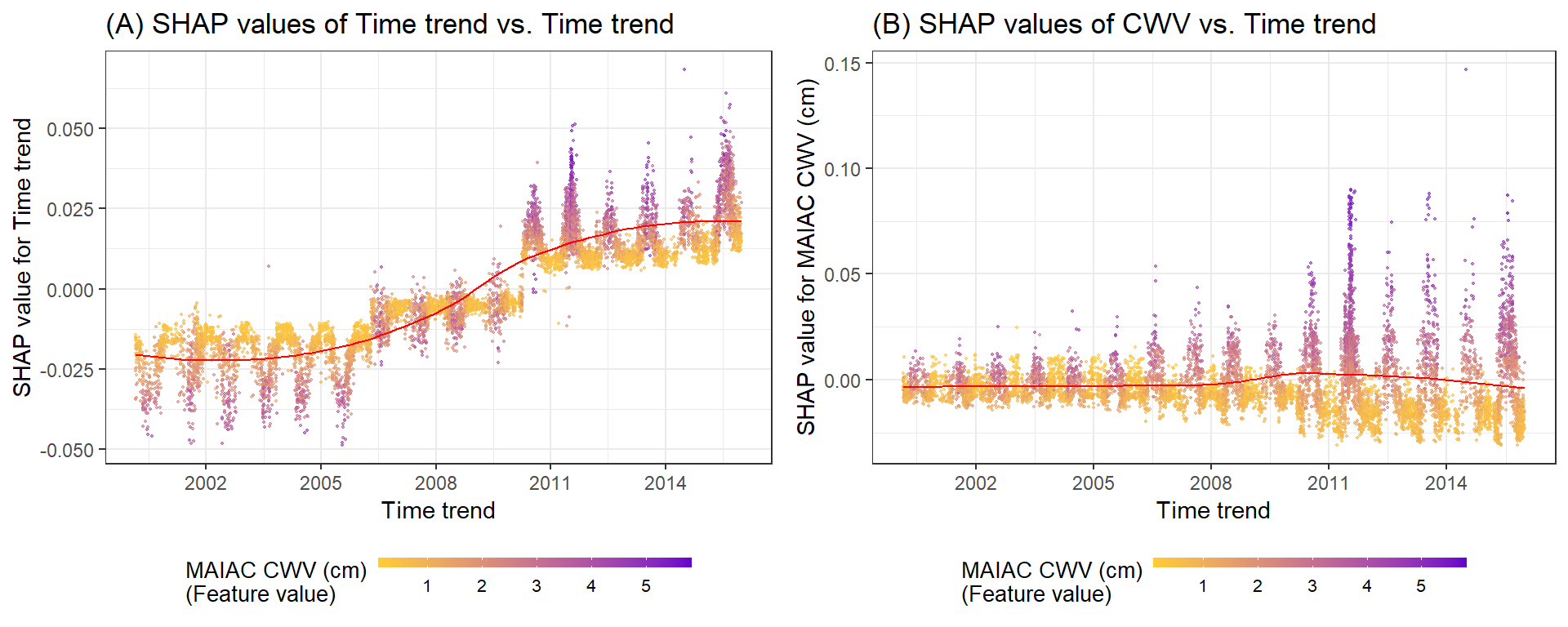

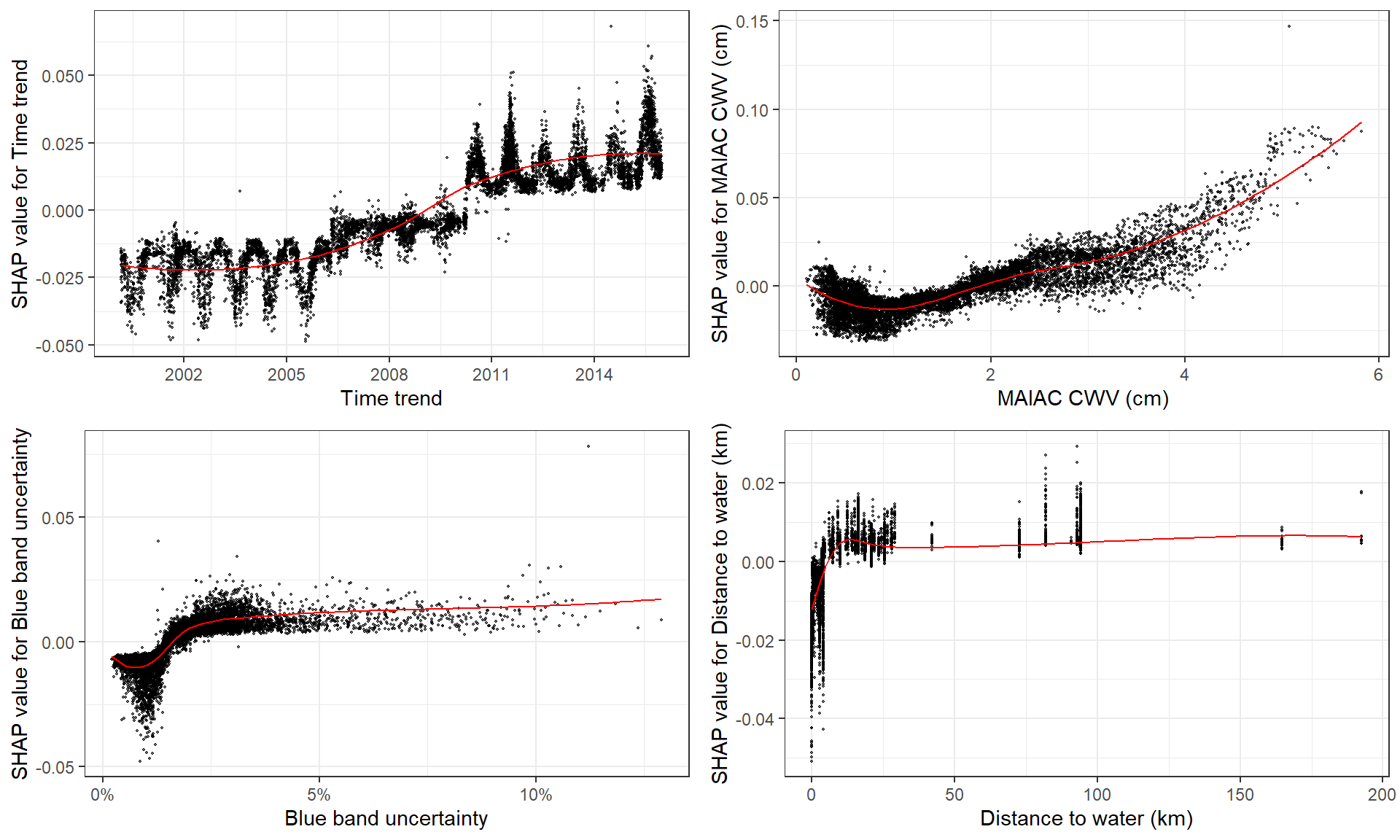

It plots the SHAP values against the feature values for each variable. Again, each dot is a station-day observation.

g1 <- shap.plot.dependence(data_long = shap_long, x = 'dayint', y = 'dayint', color_feature = 'Column_WV') + ggtitle("(A) SHAP values of Time trend vs. Time trend")

g2 <- shap.plot.dependence(data_long = shap_long, x = 'dayint', y = 'Column_WV', color_feature = 'Column_WV') + ggtitle("(B) SHAP values of CWV vs. Time trend")

gridExtra::grid.arrange(g1, g2, ncol = 2)

- SHAP values showing the contribution of the time trend to predictions. The color represents the MAIAC CWV for each observation (purple high, yellow low). The LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing) curve is overlaid in red.

- SHAP values showing the contribution of the MAIAC CWV to predictions of CWV measurement error shown across the time period of the study. Note distinct y-axis scales for Terra and Aqua datasets. The color represents the MAIAC CWV for each observation (purple high, yellow low).

Here I choose to plot top 4 features using function shap.plot.dependence.

Plot SHAP value against feature value, without color_feature but has marginal distribution:

fig_list <- lapply(names(shap_values$mean_shap_score)[1:4],

shap.plot.dependence, data_long = shap_long)

gridExtra::grid.arrange(grobs = fig_list, ncol = 2)

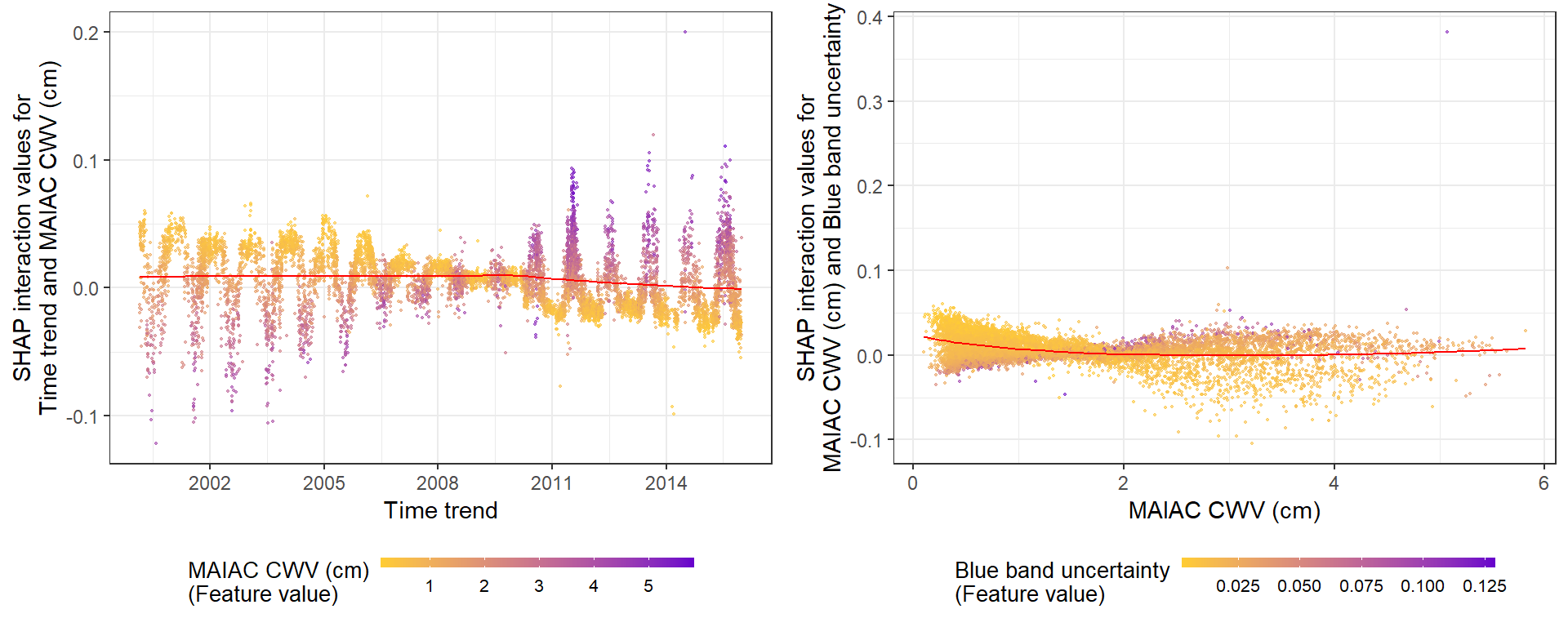

Interaction effects

SHAP interaction values separate the impact of variable into main effects and interaction effects. They add up roughly to the dependence plot.

Quote paper 2: “SHAP interaction values can be interpreted as the difference between the SHAP values for feature i when feature j is present and the SHAP values for feature i when feature j is absent.”

The SHAP interaction values take time since it calculates all the combinations.

# prepare the data using either:

# (this step is slow since it calculates all the combinations of features.)

shap_int <- shap.prep.interaction(xgb_mod = mod, X_train = dataX)

# or:

shap_int <- predict(mod, dataX, predinteraction = TRUE) # (the same)# **SHAP interaction effect plot **

# if `data_int` is supplied, the same function will plot the interaction effect:

g3 <- shap.plot.dependence(data_long = shap_long,

data_int = shap_int,

x= "dayint", y = "Column_WV",

color_feature = "Column_WV")

g4 <- shap.plot.dependence(data_long = shap_long,

data_int = shap_int,

x= "Column_WV", y = "AOT_Uncertainty",

color_feature = "AOT_Uncertainty")

gridExtra::grid.arrange(g3, g4, ncol=2)

Here I show the interaction effects between Time trend and CWV (LEFT), and between Blue band uncertainty and CWV (RIGHT).

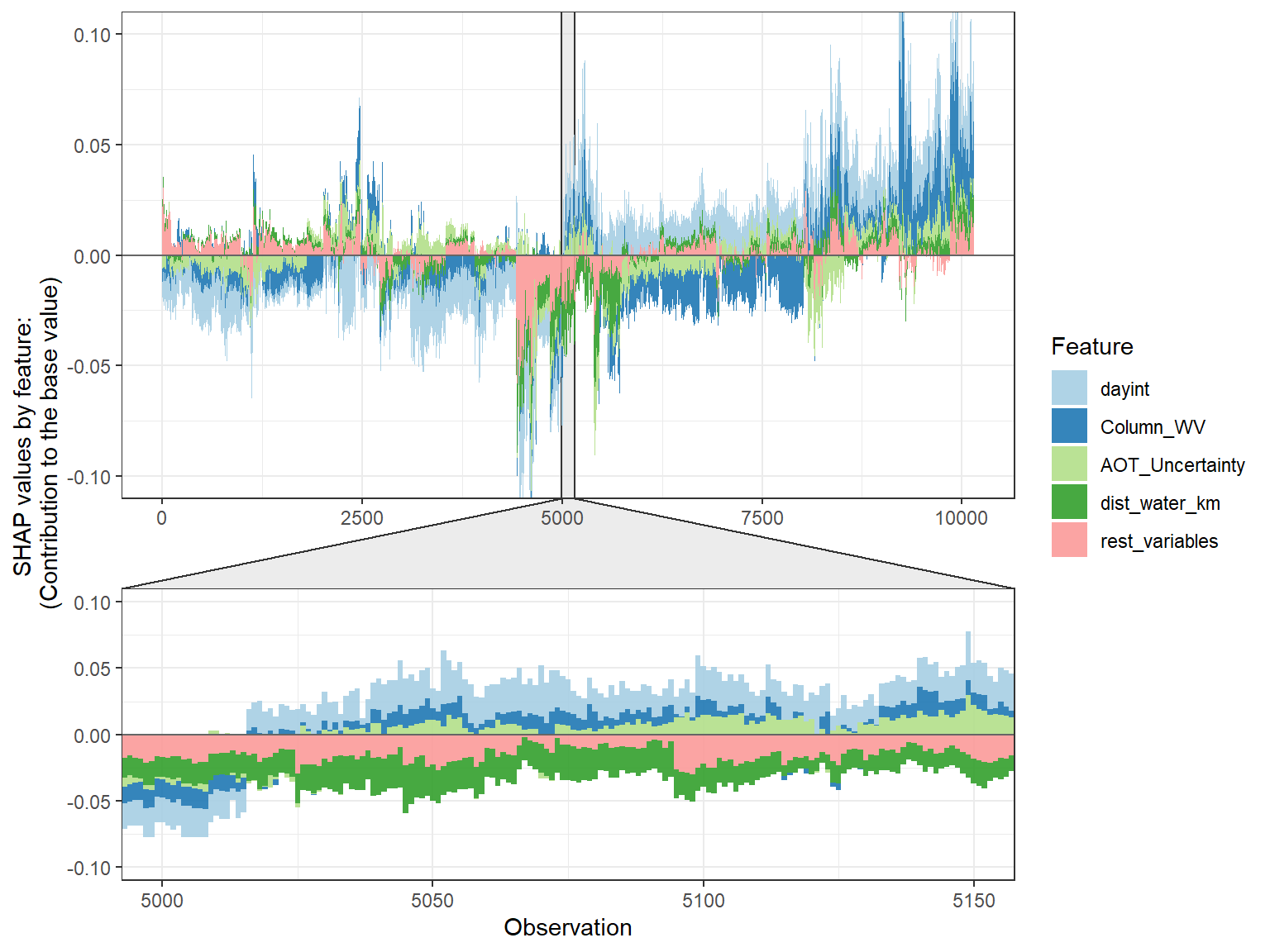

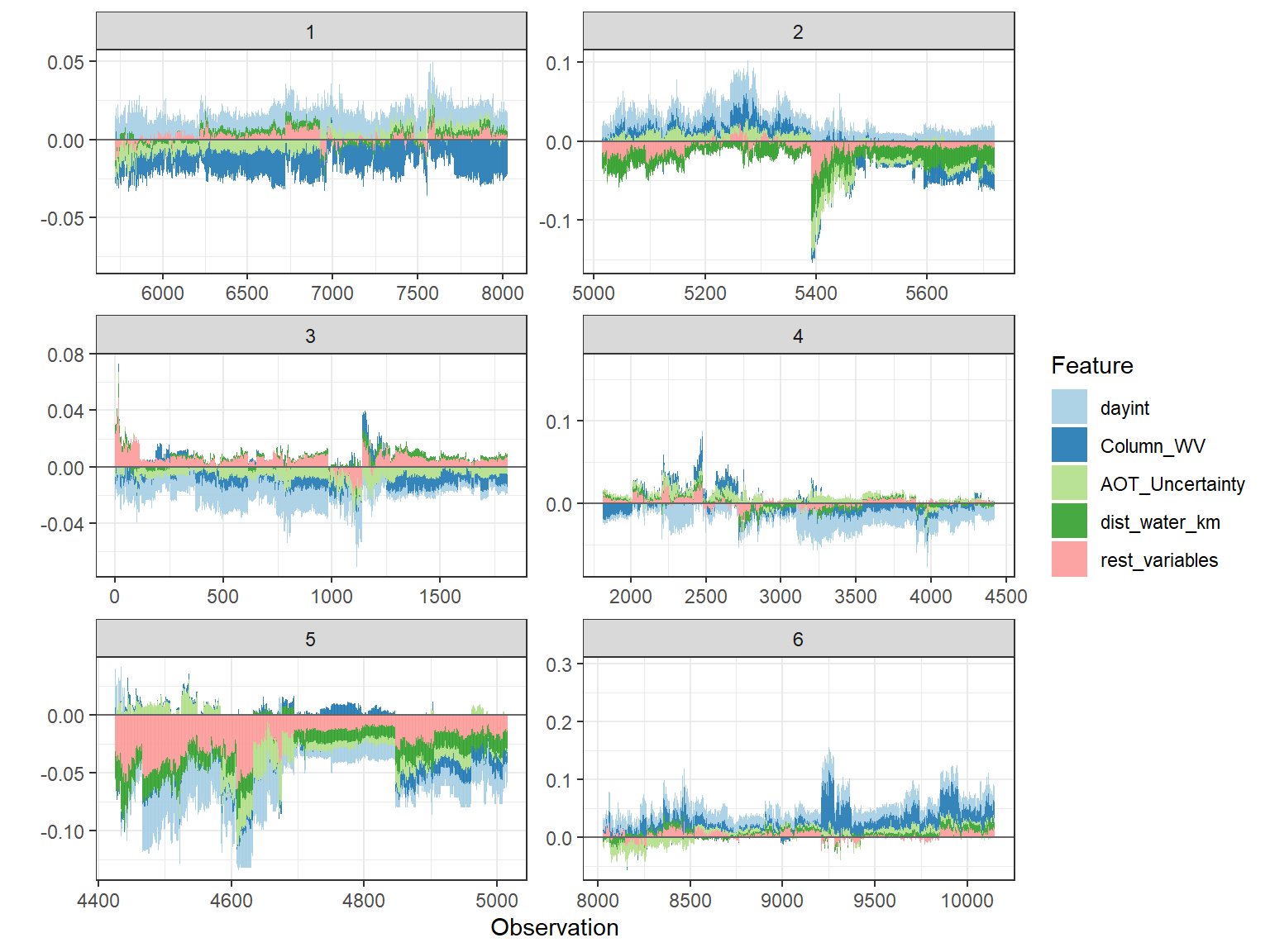

SHAP force plot

The SHAP force plot basically stacks these SHAP values for each observation, and show how the final output was obtained as a sum of each predictor’s attributions.

# choose to show top 4 features by setting `top_n = 4`,

# set 6 clustering groups of observations.

plot_data <- shap.prep.stack.data(shap_contrib = shap_values$shap_score, top_n = 4, n_groups = 6)

# you may choose to zoom in at a location, and set y-axis limit using `y_parent_limit`

shap.plot.force_plot(plot_data, zoom_in_location = 5000, y_parent_limit = c(-0.1,0.1))

# plot the 6 clusters

shap.plot.force_plot_bygroup(plot_data)

References

Recent submitted paper from my lab that applies these figures: Gradient Boosting Machine Learning to Improve Satellite-Derived Column Water Vapor Measurement Error

Paper 1. 2017 A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions

Paper 2. 2019 Consistent Individualized Feature Attribution for Tree

Ensembles

Paper 3. 2019 Explainable AI for Trees: From Local Explanations to Global Understanding